Que tal el Queso

By Deia Schlosberg

July 20, 2007

“So, how do you like cheese?”

Pause.

“You like cheese?”

“Uh, yeah. Yeah, we like cheese.”

“Alright then, I’ll come back in the morning with some cheese for you

guys.”

We threw camp together one evening as a storm rolled closer. It turned out to be all talk, and so the sky cleared enough to watch the full moon rise on our right, while moments before, the sunset had exploded in a firey horizon on our left. We cooked up our dinners as the sky grew dark, and were shortly visited by a lone man with a flashlight, who had waded across the river at night to come talk to us. Huelmes lived on a farm nearby and had seen us from a distance; he came to learn what in the world we were doing. We probably had an hour-long talk about, first, the obvious questions we always foment wherever we go, but then continuing on to politics and the environment and social trends of our respective countries. It was getting late, and though we were all enjoying the conversation, Gregg and I were especially tired and the responses were becoming more sparse in our subconscious efforts to wrap up. There was a final-seeming silence. And then he hit us with the cheese question. The next morning we packed up and hit the trail without seeing him. It was not long, however, before Huelmes rode up behind us on his horse, indeed, bearing cheese from his own cows. Good stuff it was.

This is why I keep walking. Not for the cheese. It’s the completely unique encounters like this one that I know I would never in my life experience were it not for walking through South America. Como así. This last section was perhaps the most beautiful, day after day, of the past year. If that’s possible to say. And like always, along with beauty comes burl. This was not an easy section, physically or mentally, and that made the rewards that much greater.

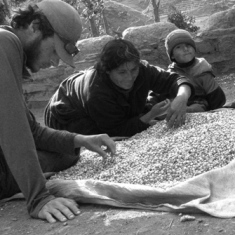

Our more significant encounters usually take the form of homestays, but this time we had our fair share of authoridades as well. These are men from the small communities who are elected (maybe?) to have the position of “Authority.” I’m not sure what this means. But several times, we have been hiking along and have been approached by a group of them, usually wanting to know where we’re going and why so they can give us “permission” to go there. Usually for us, that’s over the nearest mountain pass on a small llama trail. In southern Peru, however, these men are very skeptical and are worried that we are miners from Chile coming to take over their valley for it’s ore. I would probably have a healthy amount of fear about that as well. However, being as it is that we are NOT Chilean miners wanting to take over a Peruvian valley, it can be frustrating to tell them what we are doing and hear in reply, “I don’t believe you,” or “yes, but what are you LOOKING for?” So far, though, once we pull out our maps and journals and photos to prove ourselves, the men are nothing but kind and often invite us to stay with them for the night.

One of my favorite encounters so far was with Sergio Aguila, who was visiting his parents to help out with the sheep and alpacas. For perhaps the first time on the trip, we had a completely open discussion about religion with someone who does not consider himself Catholic nor any other official religion. He has given his views much thought and has put together a set of beliefs that are his own. That is practically unheard of here in Peru where 96.4% of the population is Very Catholic. Just the night before we were given a pamphlet about the Bible and why one should believe everything in it, which is not an unusual happening. I have nothing against any religion, and that said, I do value personal thought within or without a religion and find it exceptional when someone comes to his own conclusions despite being in a society where accouterments of Catholicism can be found in every bus, cab, restaurant, hostel, and especially every home.

We crossed our one year point in this section, and I vowed to myself to document more of the experience in writing. I take in so much from the outside—the land and people—and by creating, I want to give back some small portion of what I’m receiving.

Our first precipitation for seven months came first in the form of rain, then sleet, then snow. We hiked through the rain before arriving in a small town where we ducked into a community hall with a group of folks also evading the wetness. Lots of questions directed toward us passed the time as we waited for the sky to clear a bit. We set up camp on a wet soccer field and woke up the next morning to a transformed white, cold, muffled, quiet world. The pass we were to climb over in a few hours was all of a sudden questionable in its do-ability. We headed up the valley toward it anyway to give it a shot, as we could always turn back and wait for the snow to clear if need be. Our company as we walked was mostly llamas munching on blades of grass poking out of the white cover. A few men walked about in the silent black and white hills and we pushed upward, greatly enjoying the complete change of feel that had me thinking of my winters growing up in the Northeast. Crossing a double pass revealed the spectacular snow caps of the Vilcanota Range, only a couple days away, and beyond any expectations we had of southern Peru’s mountains. Gregg danced. We laughed in awe and took a few pictures and headed downward where the sun had begun to melt everything. Within less than an hour, our valley was green with moss and tress everywhere and sweet flower smells. A very steep descent brought us eventually to a river through karst stone, carving its way in and out of tunnels and under hanging stalactites. We camped across the river from the small town of Uchullucio, which has seen its share of gringos.

When we find ourselves on the trail of other tourists, it’s always obvious by the way the kids run out to greet us by saying, “Da me dulce.” Literally, “Give me candy.” This is the only phrase most of them know in Spanish, as we are in a predominantly Quechua-speaking area, so only those who have started school know Spanish. Whoever the moron was who began this trend of handing out sweets has got a heck of a legacy down here. We, not wanting to further this nonsense, do not carry candy with us, nor do we hand it out. We try to interact with the kids so that their only impression of gringos is not gumball machines with legs and backpacks. Usually this is fine. Once, two girls even gave US potatoes. Some of the children get rather pissed though at not having their demand met, and so one time upon leaving a town as sugar-free as it began, we had several rocks hurled at us by a seven year old. Can’t win all the time. Waking up in the morning across from Uchullucio quickly turned after school special-esque. A group of kids stood on the opposite bank of the river and stared across at our tent. When we emerged, there was a bustle of excitement. We waved and went about our morning routine. They stared. One by one the boys ran across the bridge and hid behind a shrub to get a closer vantage point. I felt rather like how I would imagine zoo animals feel. We urged the kids to come over to us if they wanted to talk. They did, again one by one. Once a sizable portion of the original crowd was gathered around us, we began to tell them how it feels much better to be talked to instead of stared at, and how we are people just like them who have to eat and go to the bathroom, even despite our light skin and backpacks. They seemed receptive to the possibility.

From there, a long day of climbing up through a beautiful canyon

(though now slightly less so due to the recent construction of a road)

brought us to perhaps the most beautiful moment of the trip. After

departing from the road we debated whether to head over the high pass

near Azungate, the second highest peak in Peru, or wait until the next

morning. It was getting late, and we weren’t sure if we could finish

the climb as well as descend steeply to a camp spot before dark. We

debated more, and ended up going for it. A long climb over snowy ground

brought the pass into clear view as the day darkened. We hurried.

Gregg, a bit ahead of me, reached the pass first, and though his face

and tears gave me some idea of what I was about to see, it was not

enough to keep me from being completely jaw-dropped breathless the

moment I stepped up onto the ridge. Azungate’s mass looked me in the

face. Across the valley and stretching out and up for miles it sat

under it’s glacial robes, with orange-purple sunset clouds to its left.

Beautiful. We flew down from our pass and found a campsite at the base

of the glacier next to one of the lakes. For the first time in over a

year, there were other campers there. There were a couple of groups

returning from weather-cancelled summit attempts and one trekking

group. But it was too cold to socialise, so we went to sleep, happy.

The end of the section was a lovely little trek with clear trails (for much of the way, which is all that can be hoped for), waterfalls, trees—even some in bright fall colors, an absolutely gorgeous mountain pass over a steep pointy ridge, an awkward homestay involving the mysterious disappearance of a bag of noodles, bright aqua lakes, alpacas galore, flowers in bloom and so on. A good two-day recap of the last month.

From here, the plan is to head to Machu Picchu to see what that’s all about, and then continue on toward Queropalca. We hope to pick up the Capaq Ñan again in a week and a half, which we will follow the rest of the way through our remaining Peru stint. The next update will most likely come from Huaraz, where we will reunite with our friends there before our brief visit with family. As always, thanks for your support and inspiration. Keep in touch.