Mummies and Monkeys

By Deia Schlosberg

October 25, 2006

Our last few weeks in Peru have been amazingly dense with rich experience – cultural, natural and historical. We began in Cohechan, a small town to the northwest of Chachapoyas, where we went in search of our first Pre-Incan archaeological site: Karajia. The region all around Chachapoyas is choc-full of ruins from the Chachapoyan civilization. Little is known about the Pre-Incan group of people beyond their taller structures, lighter complexion, and fine-tuned stone masonry skills. Despite Karajia being in every tourist poster and brochure in north central Peru, the actual site is nearly impossible to find without directions from the locals. After having to pass through a festival blockading the only street in town (each of us was grabbed, full packs and all, by an inebriated elder of the town and made to dance to the music of the little brass band for a good ten minutes before being allowed to hike on), we found the small trail that led steeply down to the site. We were led to six rather Easter-Island-looking busts, human-sized, sitting perched in the middle of a sheer limestone wall. The busts are actually sarcophaguses with mummies of respected figures inside, probably military generals. Atop two of the busts are human skulls, which we learned were the enemies of the generals inside, killed after their deaths. The most intriguing part of the site is the placement of the sarchophaguses, on a ledge that would seem impossible to get to, let alone place six huge, stone-carved figures upon.

From Karajia, we aimed our compass south and went, taking us over farmland, dirt roads, thin, muddy trails and rocky remnants of Incan roads. A long hike up to a ridge-top set us up for the most beautiful view of my life to date: Belen Valley at sunset. A deep, lush, bright green valley with a floor wide enough for a river to take broad meanders through sat capped by rays of light from the setting sun. Speechlessly, we descended into the valley as the sun did the same behind the far ridge. We spent the first half of the next day walking the length of the main valley, fording over and over again the Rio Belen as it wove in front of us. At mid day, we diverged into a side valley, soon passing by a lone, small cabin where inside sat several men, whistling for us to come over. We obliged and ended up having one of the most memorable experiences of the trip so far. We sat, sharing coca leaves and conversation with these men for some time, learning that they would also be departing soon on foot over Incan roads to head home. (Only one of the men actually lived in the cabin.) They invited us to walk with them and offered to show us some hidden ruins along the way. Before departing, though, everyone gathered around the table to share a meal of rice, beans, corn and meat—all from the same vessel, all with hands. Taking part in this meal as such was probably not the best move as far as sanitation goes, but socially it was a larger gesture than we even intended. Dionicio, whose home we were in, stepped back from the meal to tell us that we were the first gringos in ten years to stop and talk with him, in his own language even, and the first gringos ever to eat with him. As far as he could understand, everyone else passed by out of fear. We were beyond moved. All we had done was accept a gesture of kindness from this man and exchanged some thoughts and it had meant worlds to him.

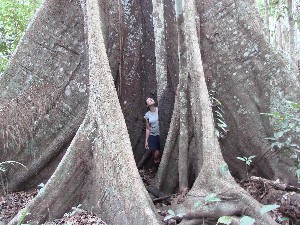

After saying goodbye, we took off with the other men on an Incan road

twisting through cloud forest. The cloud forest is a unique ecological

zone due to the combination of latitude, moisture and elevation, the

result being a lush jungle-type forest high in the mountains, and thus,

in the clouds. It turned out that Wilson, one of our hiking companions,

was extremely passionate about the history of the area, and was working

on a project to promote education of the archaeological sites, as

nothing is written in history books about the rich Pre-Incan story

here. Wilson led us through a large settlement on a densely vegetated

ridge, part of the Gran Vilaya network. The site is untouched,

unexcavated, and hundreds of stone houses and walls wait, cloaked in

ferns and moss and vines. After dropping into and climbing out of the

next deep valley, we arrived at Wilson’s sister’s house, where we spent

the night and two meals taken in as members of the family. The

following day was probably the longest unbroken climb of the trip, all

through steep, dense cloud forest. Another couple of days wandering

through forest and over dirt road brought us to Kuelap, the most

well-known and studied Chachapoyan site. Kuelap is a giant fortress on

top of a high ridge that was the home to thousands at its peak. Because

of the design, the fortress was impossible to overtake but was

abandoned and reoccupied by several groups over the years. Still, very

little is known, and only about a third of the whole site is currently

cleared and documented archaeologically. As we walked around, we easily

found hundreds of potsherds and human bone fragments. Being the last to

exit Kuelap’s wall’s at sundown (save for the llamas), we sought out a

campsite nearby and ended up sleeping at a work site down the hill,

where millions of artifact fragments with stories were washed, bagged,

boxed, labelled and stored. Entire skeletons were sitting out on

tables, clearly from the ax holes, casualties of ancient battles. It

seems it must be only a matter of a short time before lots more will be

known about these people and the history here. Wrapping up this trek,

we bee-lined for Leimebamba, our current south-point on the hike.

In Leimebamba, we made the decision to go back to Chachapoyas for medical reasons. My foot has been hurting and worsening for over a month now, and for fear of a stress fracture developing, we decided to look into it sooner rather than later. It was also necessary to make yet another attempt at ending our intestinal havoc. The return journey did introduce us first to Ted, an American from Oregon who plans to hike with us for a portion of the trek, and then to Consuela, an exceptionally generous woman who lives in Chachapoyas and offered us a room in her house as our home-base until we get hiking again. She has been lovely company and provided us with a brief home away from home, giving us tea and bread and hugs. No fracture showed up on the x-ray, so the doctor ordered rest and anti-inflammatories. Resting on a thru-hike is beyond frustrating, especially when we’re racing to beat the bad weather in southern Peru. However, we made the best of the downtime by spending a week in Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve in the heart of the Amazon basin. Absolutely amazing. After the experience there, I feel connected to the Earth and the life on it in a profoundly new way. A long bus journey ended in Yurimaguas, where to continue east, it is necessary to take boats along the major Amazonian tributaries. On the hammock-filled flatboat, we saw our first pink dolphins, happily living in a river. We also met Fillippa, yet another very kind Peruvian woman who invited us to stay with her son, Roly, and his family in Lagunas for the night while we figured out our plan for exploring the reserve. It is impossible to enter the reserve without a guide because of permit issues and for the lifetime of experience necessary to safely experience it close-up. We were lucky to meet Raul, a guide with ETASCEL, who ended up blowing us away every day with his selva expertise and observational amazingness. We travelled the reserve in canoe, with Raul in front and our second guide, great as well, Armondo, in the rear. After our jungle experience on foot in Ecuador, it became quickly apparent that the waterways are much more conducive to human navigation than trails, which are entirely artificial in an environment of rapidly-growing vegetation. The Samiria River gave us a tranquil tunnel through the dense rainforest and immediately upon setting out, we were overtaken by the symphony of bird, insect, and monkey songs, and the smells of lush plants and flowers. It was not long before seeing our first toucans, our first black monkeys in the distance, giant blue butterflies, an anaconda, on and on. In the course of our four days and nights, we saw several other species of monkey—howler, white, squirrel and pichico, crocodiles, piranhas, a rare white frog, a river otter, pink and grey dolphins, vampire bats, other varieties of snakes, turtles—including the birth of several, countless amazing birds including macaws, several fish species, huge spiders and insects, perisoso, or three-toed sloths, an electric eel, and more and more. I was acutely aware the entire time of how densely inhabited this area is, and how precious it is. Always we hear about “saving the rainforest,” enough that it has become almost cliche. But being there and experiencing the density of life present makes all the bumper stickers and t-shirts have actual meaning; having a howler monkey stop in its path above me and look down—so as to make eye contact with a close relative, now so vulnerable to extinction through habitat destruction—moved something in me. In addition to the wildlife, our daily life living off of the resources of the selva was fascinating as well. Every day, our guides (and each of us, even) spear-fished from the canoe to allocate our next meal: fish wrapped in giant leaves and cooked over a fire with yucca or plantain. We learned which type of bark to use for rope to construct a shelter in a sudden downpour, how to get rubber from rubber trees, which bark to use for a stomach-settling tea, which palm fronds make the longest-lasting roofs, and other useful bits, it seemed, almost hourly. Throughout the four days, I felt a very comforting sense of being home in the jungle. I know I will go back at some point. We spent one more night with Roly and his generous family before taking off on the return boat to Yurimaguas. Here we met Beth, Peter, and Ko, two Australians and a Canadian, respectively, travelling to help where possible and to learn; we made some easy conversation and appreciated the company. The plan from here is to resume the hike on an Incan road heading south out of Leimebamba. We’re very much looking forward to foot travel again, as well as highly anticipating the arrival in a few weeks of our great friends from home, Dave and Jessie, who plan to hike with us for a month or so. And, as always, we miss and love our families and friends and think of you guys often.